Dr. Sharmini Coorey is a non-resident fellow at Verité Research. She was a former Department Director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and currently a member of the Presidential Advisory Group on multilateral engagement and debt sustainability advising the Government of Sri Lanka.

Part I of this article laid out the grim fiscal and debt sustainability outlook for Sri Lanka. Part II concludes by suggesting policy priorities to help Sri Lanka escape this debt trap.

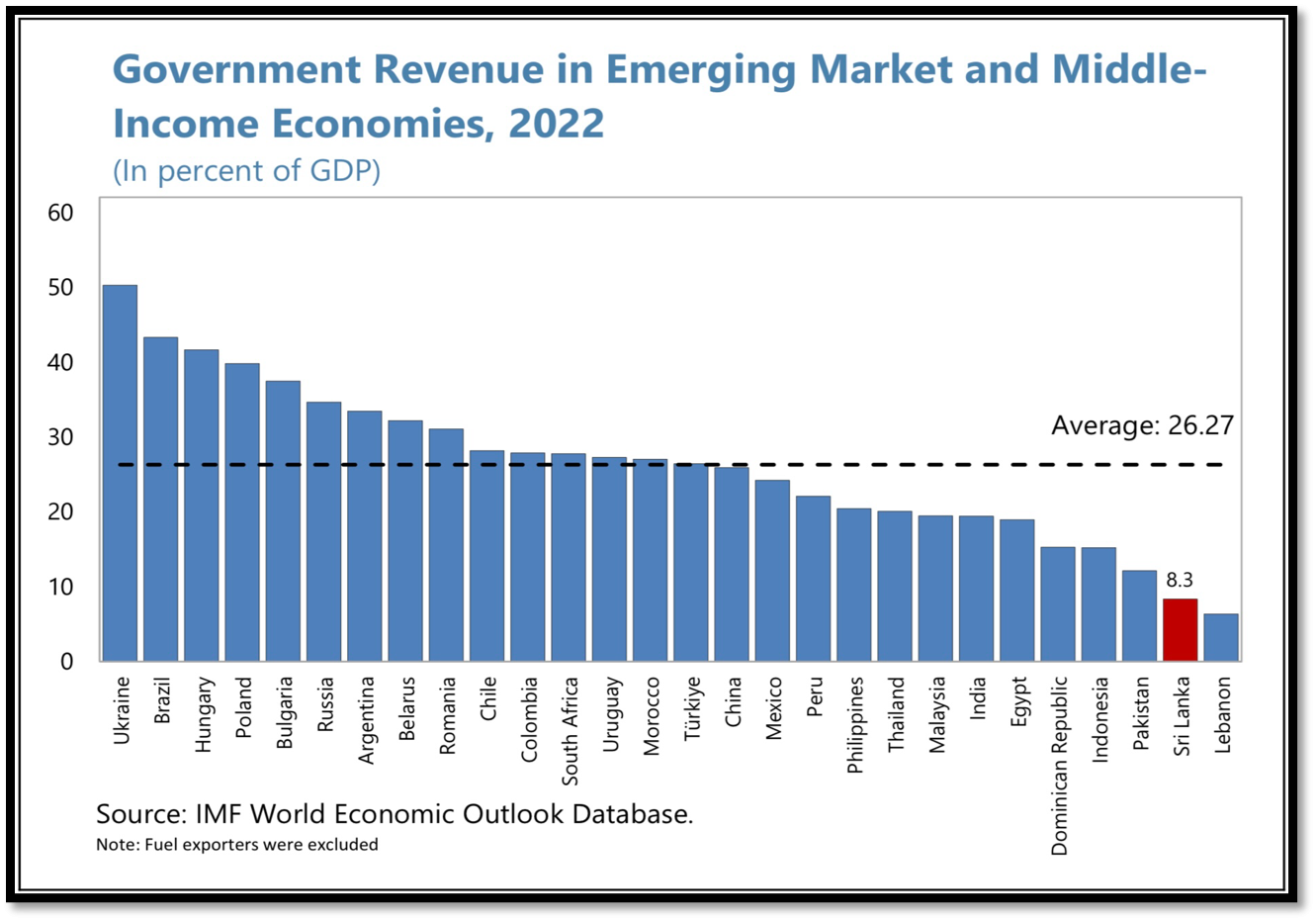

The key driver of debt dynamics is the gap between real GDP growth and real interest rates on government debt. Sustained annual growth of 5-6% and low real interest rates through disciplined fiscal policy would significantly improve debt sustainability. With slowing labor force growth due to an ageing population, sustaining high GDP growth requires increased investment and productivity growth. In addition, raising Sri Lanka's low tax ratio to 16-18% of GDP, aligning with Asian peers, would support sustainable non-interest spending levels (Figure 1 - Given below).

Sri Lanka needs to adopt a new economic paradigm

Given the imperative of fiscal discipline, Sri Lanka can no longer turn to the economic model of the past where growth was driven by public sector spending fueled by borrowing and inward-looking, protectionist trade policies. It needs to adopt a new economic model where growth would be:

Clearly, multi-year reforms are needed to achieve such growth. Recognizing the political uncertainties ahead, the priority now is to establish the legal frameworks that will commit future governments to good governance. Sri Lanka lacks robust laws and legal frameworks to ensure sound processes for making and implementing economic policies as well as independent and accountable economic institutions protected from political interference. It will be important this year to:

1. Safeguard the independence of the CBSL. The Central Bank Act (CBA) of 2023 is an example of a legal framework that promotes good governance—in this instance in monetary and financial policies. Upholding the CBSL’s independence, provided under the CBA, becomes paramount, especially if election promises press for funding fiscal deficits through money printing. Challenges loom for the CBSL, including from VAT, electricity, and energy price hikes, the weak economic recovery, and external shocks. Managing deviations of inflation from the target over the medium term is best left to the Monetary Policy Board’s expertise.

2. Lay the foundation for fiscal sustainability through better governance on tax policy and administration.

On tax policy:

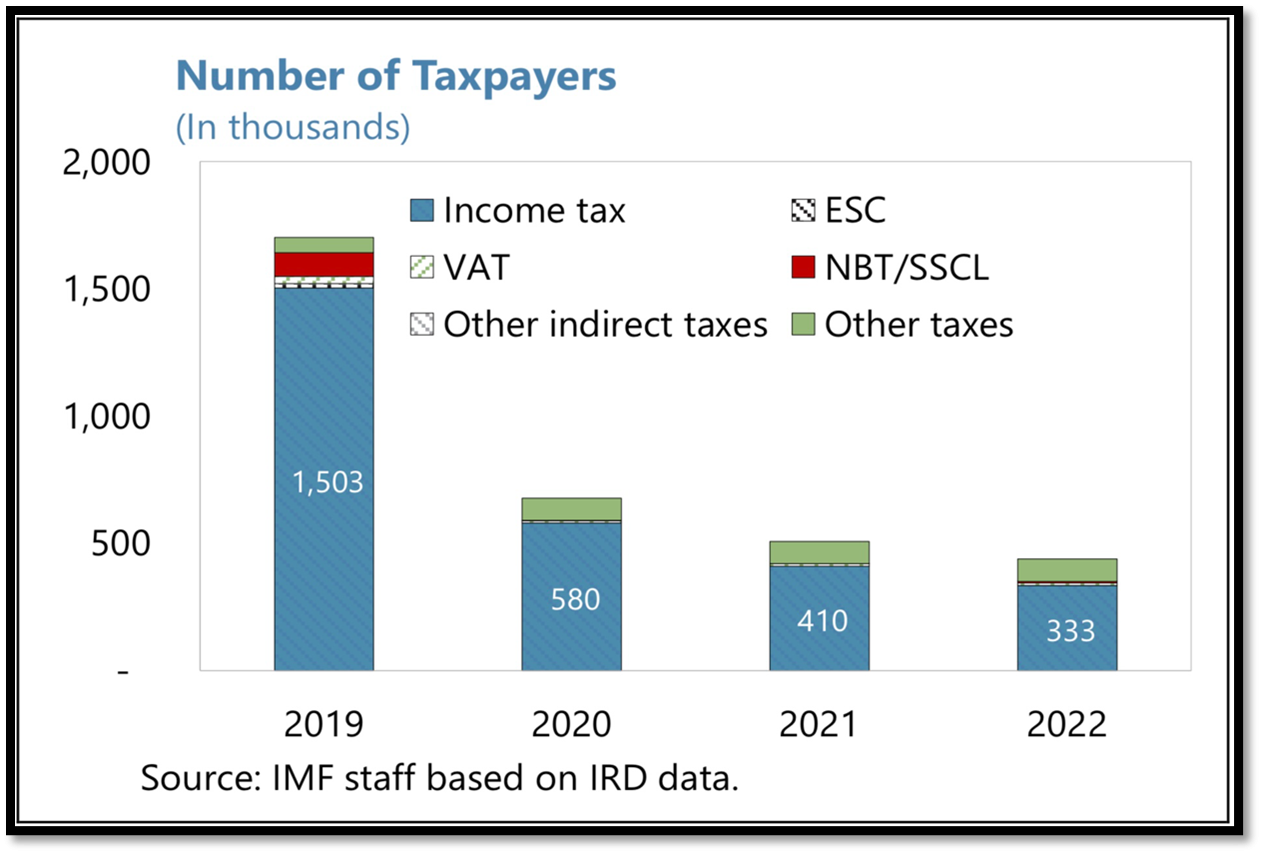

On tax administration, The sharp drop in taxpayer numbers post-2019 tax reductions caused tax revenue to decrease from nearly 12% of GDP in 2019 to 9.2% in 2023. Mandating taxpayer identification numbers for transactions such as property, importing, and professional services and digitizing tax collections by IRD, Customs, Excise, including fully operationalizing the RAMIS system, are essential. Adequate staffing and empowerment of the Large Taxpayers Unit and the new High Net Worth Individuals Unit are critical, possibly through salary bonuses to attract private sector expertise. Parliament should pass legislation for stronger tax administration, including criminal penalties for tax evasion and bribery.

3. Strengthen governance over spending and reduce the role of the public sector:

A strong legislative agenda to establish legal frameworks for better fiscal policymaking and a competitive economy needs to be embraced by all political parties. Sri Lanka has no time to waste given the harsh reality of its fiscal predicament (see Part 1). Jumpstarting a growth dynamic that is independent of government and ensuring good governance over fiscal policy are essential if the country is to avoid another, far more painful, debt restructuring. This is not a time for politics as usual.